In her 60s prime, Nico was the formidably beautiful Wagnerian queen of avant-garde rock, breaking not only the hearts of her fellow Velvet Underground bandmates, John Cale and Lou Reed, but inspiring Jackson Browne and Leonard Cohen to write some of their best songs. Alas by the 80s, she was barely a cult survivor – addicted to heroin, trying to reconnect with her son by Alain Delon and touring with a motley crew of young musicians in dives across Europe.

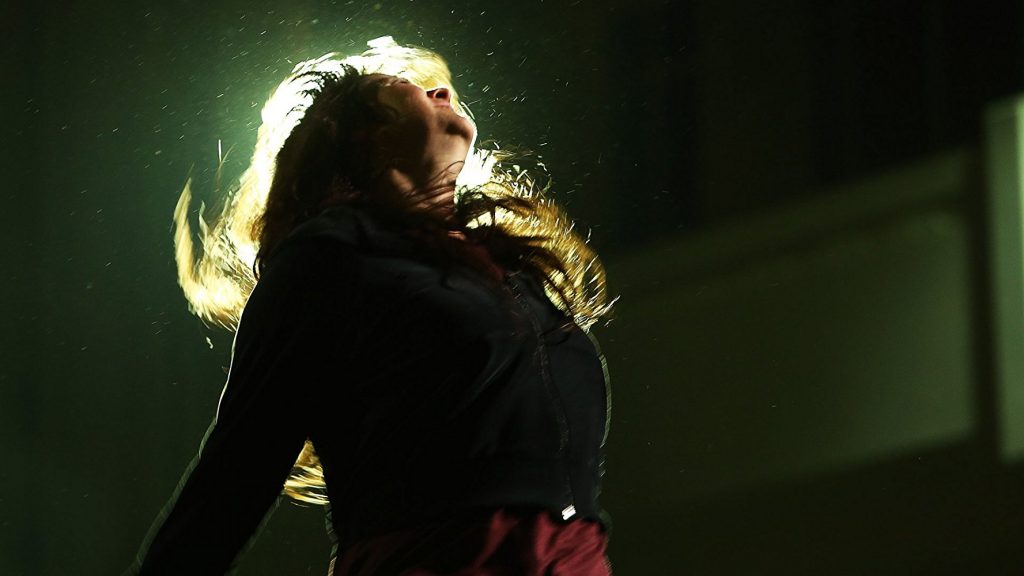

Italian director, Susanna Nicciarelli, largely sets Nico’s life story in these final days before her accidental death in Ibiza, but we catch glimpses of the heady glamour of the Velvets and Andy Warhol’s Factory through archive footage. Despite a charismatic performance by Danish actress, Trine Dyrholm, in the title role, this film never quite solves the problem of making Nico’s aimless life dramatically compelling. While Dyrholm is supported by a strong cast of supporting players including John Gordon Sinclair as Nico’s long-suffering manager and Annamarina Marinca as the band’s vio-linist, their efforts are not rewarded by a script that largely consists of grim vignettes of life on the road.

Nico 1988 is a problematic film to recommend to both general audiences and those familiar with Nico’s story through musician James Young’s memoir, Songs They Never Play on The Radio, or Richard Witts near exhaustive biography. While no one can accuse Nicciarelli of playing fast and loose with the facts, as is often the case with biopics, there are not enough scenes that give us an insight into how Nico went from icy blonde femme fatale to a near apathetic junkie with seemingly no other life beyond the stage and her addiction. And while it is important to acknowledge that such puzzles exist in real life, this film fails to give us any clues as to where the cold beauty and grandeur of Nico’s music came from and more importantly, why she continued to perform and compose when she had seemingly given up on so much of the rest of her short life.